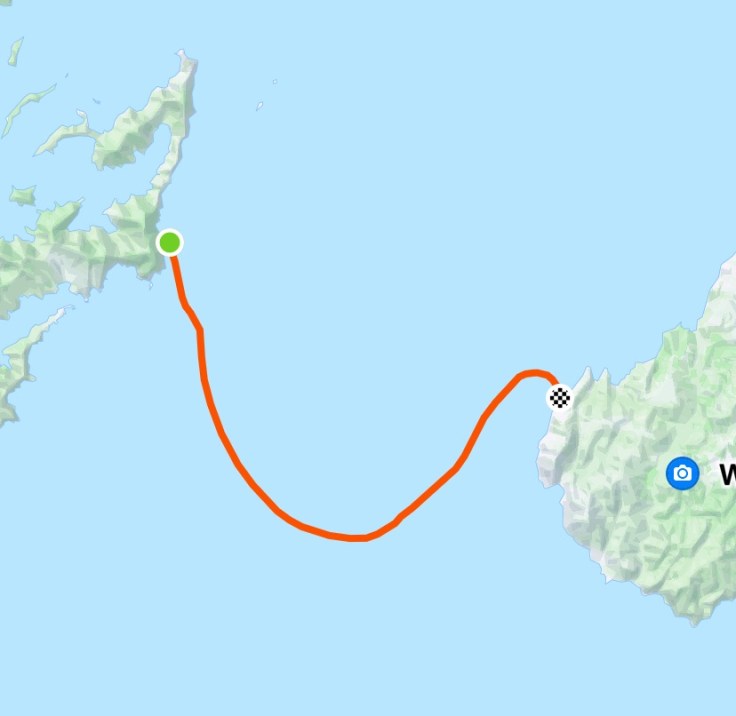

On February 6th, 2025, I had the absolute pleasure of swimming the Cook Strait (Te Moana-o-Raukawa in Māori). This dynamic body of water flows between the North and South Islands of New Zealand, connecting the Tasman Sea and the South Pacific Ocean. It is known for having unpredictable currents, cold water, and lots of marine life. The official swim route is between Arapaoa Island on the South Island and Cape Terawhiti on the North Island, and can be swum in either direction. The strait is 14 miles across at its narrowest point, but my swim ended up being about 23 miles due to the currents.

Serendipity in Marathon Swimming

In 2024, I spent three incredible weeks in Oceania – two weeks vacationing with my wife, Deedee, in New Zealand, and one week in Sydney at a swim camp hosted by the Bondi Icebergs. While in New Zealand, I received numerous messages asking if I was there to swim the Cook Strait. At that point in time, the Cook Strait truthfully wasn’t on my radar. Deedee and I did hope to return to New Zealand eventually, but not anytime soon, and purely for leisure.

PC: Kevin Buckholtz

While still in Bondi and just a few days after leaving New Zealand, I received an unbelievable text message from my good friend, Conny Bluel. She had booked with a local pilot to attempt the Cook Strait in 2025, but her circumstances had changed, and she was offering me her slot. I immediately called Deedee, who was both amused at the serendipity and thrilled at the opportunity to return to New Zealand much earlier than either of us would have ever imagined.

The Before

We arrived in Auckland, New Zealand on the 29th of January and spent the first few days of our trip having some incredible adventures. On the 4th of February, my pilot, Grant Orchard, reached out to me. Unfortunately, the weather wasn’t looking favorable during my swim window, which was originally set for the 11th to 14th of February. We discussed the possibility of getting to Picton early and whether I would be comfortable swimming at night. We were in Wellington, so getting over to Picton via the ferry could be easily arranged. However, the mere mention of swimming at night had me feeling severely uneasy. For various reasons, I really struggled during my Catalina Channel swim, to the point that I considered quitting marathon swimming altogether. I thought I had since moved past that sentiment, so was surprised to be experiencing such a negative visceral reaction to the prospect of swimming at night.

I called my training partner, Maja, who helped me process how I was feeling and decide how to proceed. I realized that though possibly controversial, I needed to make the decision that was best for me within the realm of what was being offered, even if that meant forfeiting my opportunity to attempt the Cook Strait in 2025. Marathon swimming is an incredibly challenging sport, and there are times to push yourself out of your comfort zone and times to recognize your limits. I didn’t put in the work to prepare for a night swim, and therefore wasn’t mentally prepared for one, so I planned to decline the opportunity to swim if going through the night was the only feasible option.

Thankfully, before I could message Grant to explain my thoughts, he let me know that the daytime weather on Friday the 7th appeared to be suitable for an attempt. In a flurry, I rearranged our travel plans and then took a short nap. When I woke up, Grant had messaged again. The weather on Friday was now looking poorly, and we would swim on Thursday the 6th. That meant that Deedee and I would need to catch the ferry the very next day!

I spent the 2.5 hour ferry ride excitedly exploring every corner of the Interislander and admiring the body of water I would soon attempt to swim. It was surreal seeing both islands and the entirety of the Cook Strait, especially when I spotted Grant’s boat out with another swimmer. This reminded me of flying over Lake Tahoe en route to Ireland a few months before my Length attempt in 2023. It is hard to conceptualize how long these swims really are until you see them in their entirety from a boat or plane!

We settled into the Waikawa Bay Holiday Park in Picton and Deedee promptly took a long nap. I used the alone time to prepare my feeds and get our equipment in order. Generally, this process brings up some nervousness, but I felt a deep sense of peace about this swim. I was confident that I had everything I needed for a successful swim, and that Deedee would take great care of me if anything unanticipated happened while I was in the water. While this swim posed some new challenges for me, namely being my first international marathon swim attempt and first swim scheduled on a flexible window instead of a set date, I trusted that my prior experiences prepared me well to handle these new variables.

The During

I got a great night of sleep and woke up at 0345 full of excitement for the adventure ahead. After the safety briefing and tour of the boat, Katabatic, we embarked on a 1.5 hour ride to the swim start location on Arapaoa Island. Grant pointed out interesting landmarks along the way, including salmon and green lip mussel farms and the defunct Perano Whaling Station.

Before getting in the water, Deedee helped me apply sunscreen and Sudocrem. I had failed to pack the 40% zinc Boudreaux’s Butt Paste I usually use for protection from chafing and sunburn, and was a bit worried the 20% zinc Sudocrem would not be strong enough to withstand the powerful New Zealand sun. I was given instructions about the logistics of the swim start by my observer, Simon Olliver. There was no safe area for me to exit the water, so my swim would start when I touched a rocky area and raised my arm from the water. I was careful in my approach and allowed the swell to carry me towards the rocks so I wouldn’t crash into the island. The water was about 59F and a bit choppy, similar to the conditions where I train in the San Francisco Bay. I could see myself moving further from the dramatic cliffs of the South Island, and soon I couldn’t see any landmarks around me. The swim was well underway!

In the spirit of being flexible, I agreed to make a last minute change to my feed plan. The currents are quite strong at the beginning of the swim and the boat crew wanted me to get as far from the island as possible before stopping. I typically feed every 30 mins, but we decided to start at 60 minutes instead. At the first feed, Captain Grant asked me to swim a bit closer to the boat. I later learned that he wanted to make sure I was within range of the Shark Shield, an electromagnetic device used to deter any curious creatures. Soon after the first feed, I took a painful jellyfish sting to the back of my neck. I audibly yelped but continued swimming. The next time I breathed towards the boat, I saw the whole crew on the back deck with concerned looks on their faces. Deedee told them that I can be vocal during swims, and that I would stop and report if anything was truly wrong. She sent out an antihistamine with my next feed, which proved to be very necessary as I accumulated quite a number of stings over the next two hours. I could see various species of jellyfish all around me and I was nearly always touching one with some part of my body. This was definitely the most jellyfish I had seen in any area of water before! Intermittently, there would be a flurry of small gelatinous objects speeding towards me in addition to the larger jellyfish. It looked like a blizzard and felt like I was swimming through boba! Corrina later informed me that those were most likely salps.

Even with taking a few jellyfish directly to the face, my mental state was very good. I passed the time by singing songs from Wicked, Six, and Hamilton and enjoying watching the massive albatross flying around me. One bird in particular seemed to learn my feed schedule, and would swim along behind me as if hoping for a treat. At one point, I noticed my crew fidgeting with the Shark Shield and looking off into the distance. I was beginning to worry if they had seen a shark, so I stopped to quickly ask and hopefully put my anxiety at ease. Thankfully, they were simply admiring a pod of common dolphins while changing the device’s battery. This was an affirming practice in not allowing my mind to spiral out over uninformed inferences made from the water! The pod of dolphins soon came to visit and swam around me for a few minutes.

Mentally and emotionally, swimming the Cook Strait was proving to be an absolute joy. I was in a positive headspace and I felt so honored to be swimming in such a magnificent place. Everything was going well and I kept myself centered with frequent reminders that the swim is not finished until I arrive at the beach. At any moment, a wildlife encounter or change in conditions could end the swim. I stayed humble and present and moving forward, swimming in 30 minute increments from feed to feed. Each time I would stop for nutrition, crewmember Don would ask me a simple math question to ensure my mind was still working and I wasn’t developing hypothermia. I got such a boost of energy from his genuine excitement at my correct answers.

After about 6 hours of swimming, I was able to see the North Island peeking over the boat on my left hand side. I have learned from experience that land is always much further away than it looks, and it’s best not to make predictions about how much longer a swim may take to avoid frustration. Strangely, I quickly lost visualization of land, but soon after began seeing land over my right shoulder. I wasn’t sure how this perspective was possible, but I continued to be able to see land intermittently for the next few hours. It didn’t ever seem closer, and I considered the possibility that I may be stuck in a strong current. I kept my head down and pushed forward, trusting that Grant’s expert knowledge of this water would lead me through eventually.

Next, the water became energized with chop that reminded me of the Potato Patch under the Golden Gate Bridge, a shallow area where upwelling creates chaotic conditions. My body was being pushed and pulled in every direction and it felt near impossible to maintain my form. Grant explained I was in a bit of a rip current and that he was angling the boat to try and get me out of it. At this point, I began to worry whether I would be able to overcome the power of the rip and make it to the North Island. I have heard various stories of swimmers being stuck in place for sometimes hours during a marathon swim without making forward progress, but I had never yet experienced that on a channel crossing. I began to think about all of the training swims in San Francisco where I would swim towards the Golden Gate Bridge while the tide was coming in, effectively putting myself on a treadmill. During those swims, I would purposefully breath towards San Francisco so I could gauge my painstakingly slow progress forward. This mental and physical exercise proved useful at this point in the swim where my pacing dropped from ~1:15/100m to ~2:20/100m for about 3k.

Soon after I was through the rip, Deedee gave me a feed and said, “KB… make this a FAST feed because this is your LAST feed!” This statement is an ode to a swim years prior when I misheard an encouragement to take a “fast feed” and then spiraled for many hours wondering how I managed to need multiple more hours of nutrition after an anticipated imminent finish. Crew, be careful what you say to your exhausted swimmers!

Grant told me to push hard to the finish, so I put my head down and swam the hardest I could. I saw the crew put the inflatable rigid boat (IRB) into the water, and Don motored up to my right. Simon appeared on the bow of the main boat directing me like an air traffic controller. He later told me that the water was pushing me south, and he was trying to turn me towards the north to avoid having me swim any additional distance. Eventually, the main boat could not continue with me any further, so it was just me and Don on the way to the beach. I started to see rocks covered in colorful sea moss below me and reminded myself that the swim isn’t over until I am on dry sand. When the water was shallow enough to stand, I carefully stood and walked up the slippery rocks until I was fully out of the water. I raised my arms and the horn was blown on the boat, signaling the official end to my swim. 8 hours and 43 minutes after I began, I had successfully crossed the Cook Strait.

I swam up to Don in the IRB and he asked, “I suppose you’d like a ride back?” I replied in affirmation and we laughed together about how ungracefully I plopped into his boat. Once I was back on Katabatic, the crew showered me with love and Deedee helped me remove the still thick layers of zinc. The Sudocrem I was so worried about had worked brilliantly and I had no sunburn! I laid down in the cabin for the 2.5 hour ride back to Picton, beaming with pride at what I had just accomplished. I swam with steady effort and a stroke rate of 62-63, a bit higher than my normal 58-60. My pacing was consistent excluding the time I spent in the rip current. The water was 59F at the start and around 64F at the warmest point, and I wasn’t cold during or after the swim. Overall, this swim was an incredible experience that amplified my love for marathon swimming. I am very thankful to Conny for giving me the slot, Deedee for being my always incredible support system, Grant and crew of Katabatic Charters for keeping me safe, and my community for supporting me as I pursue my goals.

The After

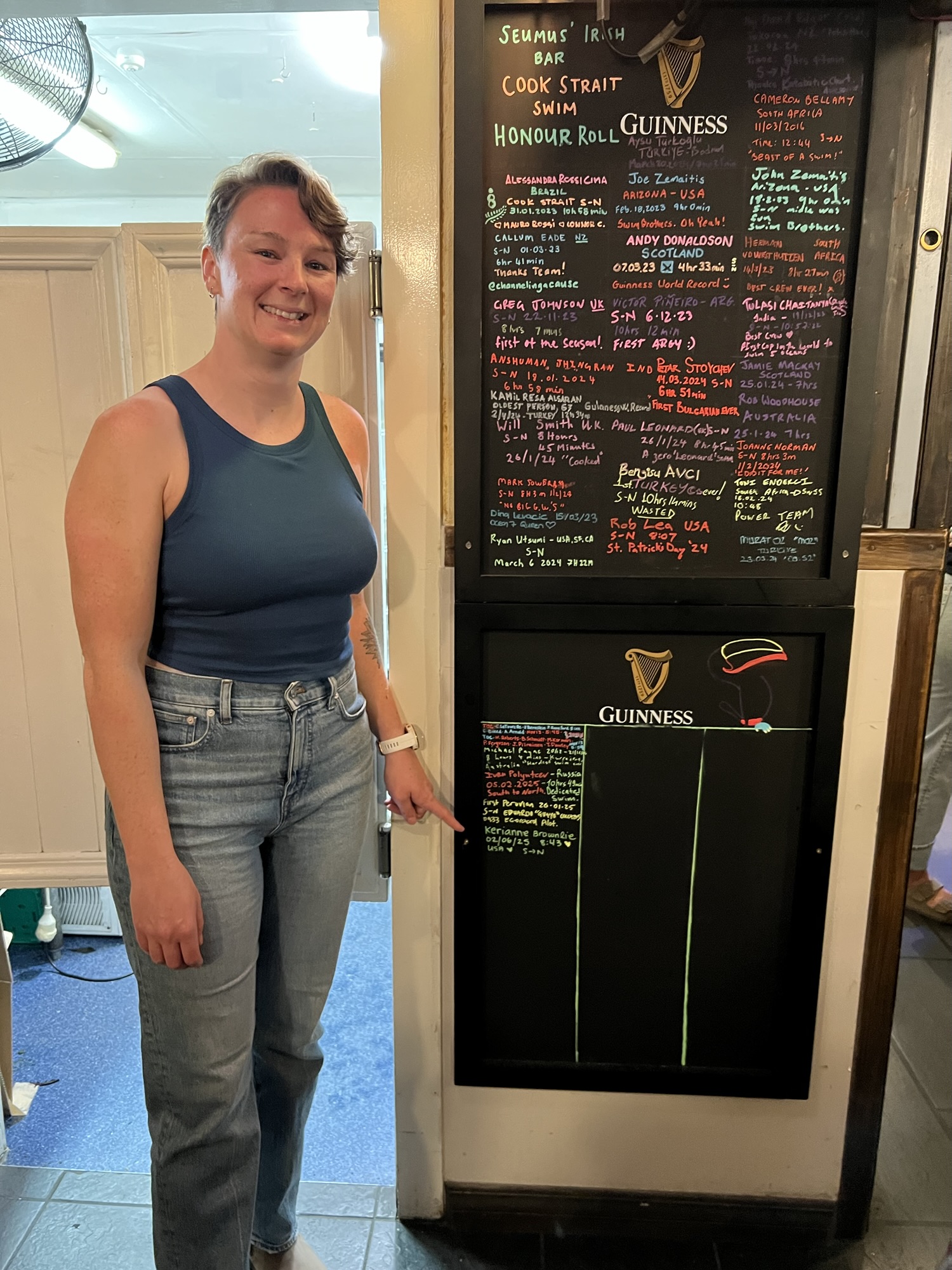

A few days after my swim, I added my name to the Cook Strait honor roll hosted at Seamus’ Irish Bar in Picton. I was then interviewed by Aitana Forcen-Vazquez of Swimming the Strait Podcast. Take a listen and let me know what you think!

Leave a comment